How my kids acquired language & built reality

Published 2025-04-27

Some discourse lately about whether LLMs (Large Langauge Models, aka “artificial intelligence”) are capable of “understanding” the meanings of words occasioned me to reflect on the way our kids developed language and a working relationship with external reality.

Language and meaning are related. We name things as we recognize them as separate from other, similar, things. English speakers didn’t need a word for “orange” (“yellow-red” worked OK) until there were enough “yellow-red” things in England that people felt the need to find a word for that specific color.

Each of the kids acquired language, and thereby constructed meaning, in different ways.

We were worried that Orion (the oldest) was not developing language “on schedule.” Until nearly his first birthday, he didn’t make babbling noises, just (we thought) inchoate shrieking, or no sound at all. In retrospect this was just newbie parent worry; I think we didn’t recognize what infant “speech” sounds like. Our pediatrician suggested he take a hearing test, which he easily passed.

Sometime around his first birthday, Orion began saying words as we recognized them. He would point at a thing and name it, emphatically. He wasn’t asking for an apple, he was announcing “that is an apple.” (“Apple” [“app” or “appa”] was his first word that we recognized, other than “mama,” of course, which is most kids’ first word.) He would narrate the world like this as we went places and did things. “Car!” “Dog!” “Bubbles!” When this pattern became apparent we realized he had been saying “words,” in the form of onomatopoeias, for several months. His word for “car” was “vroom,” his word for “cat” was “mrooww,” etc. He even had an all-purpose placeholder (“that,” rendered as “dap”), which he would happily use — in the declarative sense — when he didn’t know the English word for a thing. We learned that when he said “that,” he was really asking “what is that?” Gradually he began to string these words together, again for basically narrative purposes. “Dog drinking.” “Man go inside.” “Bird eat that.”

Iris built language in a totally different way. (Moments after Iris was born I realized she was already a different person than Orion.) At just a few months old, she organized her sounds with a cadence eerily like conversation. They were’t phonemes, just goos and gurgles, and there was no attempt (as far as we could hear) at meaning. She wasn’t trying to convey anything all…but she would look directly at you and start making a sentence. Gradually, and with no moment where we thought “this is her first word!” she started subbing in real language sounds, and then real words for goos and gurgles. I remember vividly taking a hike through the forest with her in the Ergo carrier around age 1, and the whole time we carried on a “conversation,” with her gooing and ba baing, and me going “oh really!?” and then her replying with goos and ba bas that had the exactly tone of “yes, really!”

Ada was probably the most textbook-like in her language acquisition. We sometimes forget that, as the youngest, Ada was seldom alone with an adult; her siblings were simultaneously models, translators, and rivals (for attention). As an infant, she babbled with single sounds until the sounds began to approximate phonemes. Most of her words seemed to be demands, or calculated to provoke a reaction from people around her. Eventually she began using single words in an imperative mode. Her first (non-“mama”) word was “Ada.” (As in, “pay attention to Ada). Then she started to string words together into couplets (“eat apple,” “go play,” “dog big” etc.) to refine those meanings and provoke more subtle reactions.

Ada was (sometimes still is…) apt to talk to herself, having small conversations under her breath narrating her thoughts or actions. If no human person would talk with her, she would happily talk with the toys, our dogs, or herself.

Ada is also the most talented linguist. She has the best Japanese of all the kids, and has retained most of her Spanish. From an early age she wrote a lot in English. She started preschool very young (age 2) and had two olders siblings to sponge from. She seemed to learn osmotically. I remember going to Burgerville with her when she was three — before she was “reading” in preschool. The prize in her kids’ meal was a packet of thyme seeds. Unprompted, she sounded out the letters: “tee-mee, tye-mee, tuh-hye-mee…”

When did our kids begin to construct a relationship with external reality?

A classic tell that kids are forming a relationship with external reality, is when they begin telling conscious lies: they know what reality is, and are choosing for a (usually selfish) reason to narrate the opposite. My kids all began telling lies like this (“not me,” “it broke by itself,” “[I did] not eat [the] cookies” etc.) around age 2 or 3. But I don’t think lying in this mode takes a comprehensive understanding of reality, as something separate from, and not dependent on themselves. Transactional lies serve a selfish purpose. Dividing “myself” from “everything else” is like Level 1 Consciousness. Level 2 means imparting the other things with their own relationships to reality.

Level 1 Consciousness: I am distinct from other things, including other people.

Level 2 Consciousness: Other people have also made this distinction; their version of “other things” includes me

I think the tell for when my kids reached Level 2 is when their random art scribbles began to depict actual people or things. In other words, when they began to create representational art. They were recognizing that when “someone else” looks at “me,” they are seeing another person.

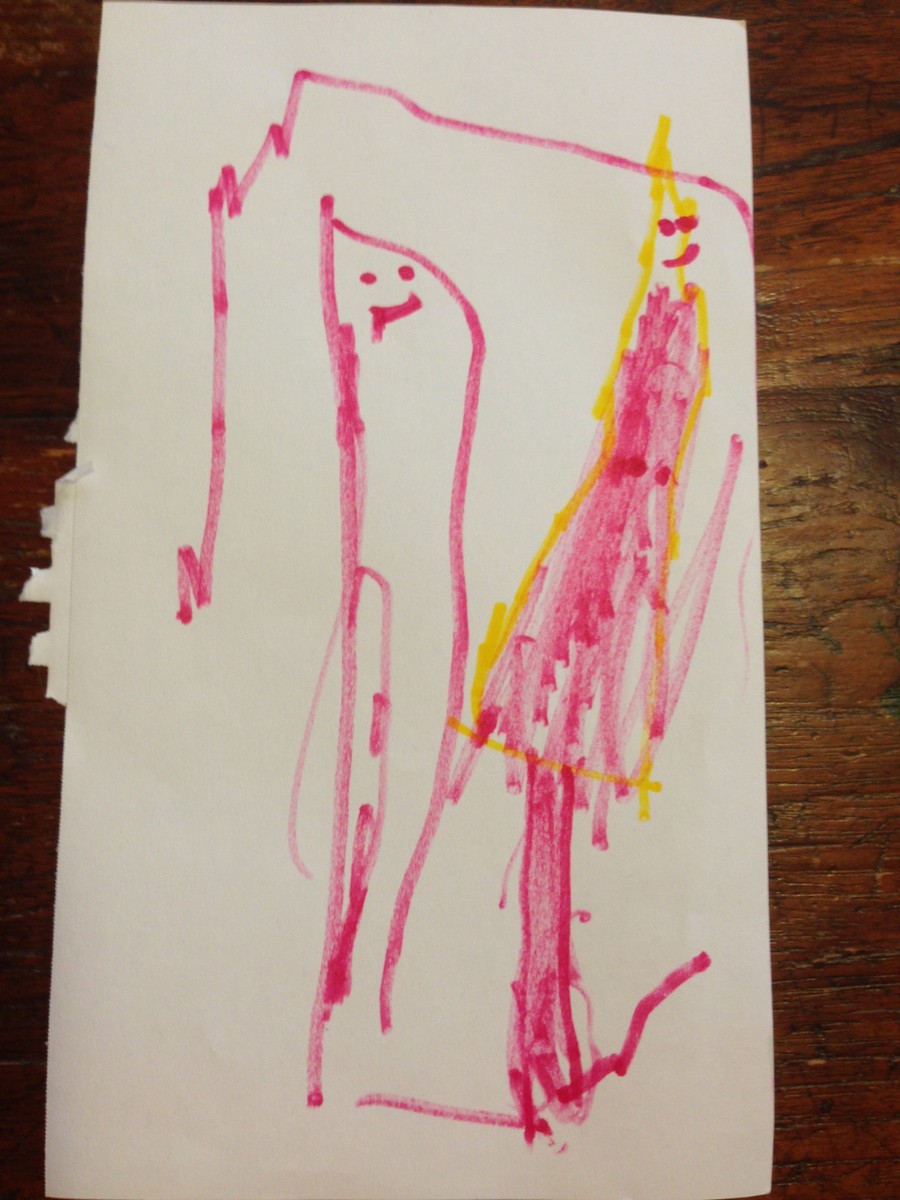

Ada’s first piece of representational art, that we recognized, was a portrait of herself and Iris:

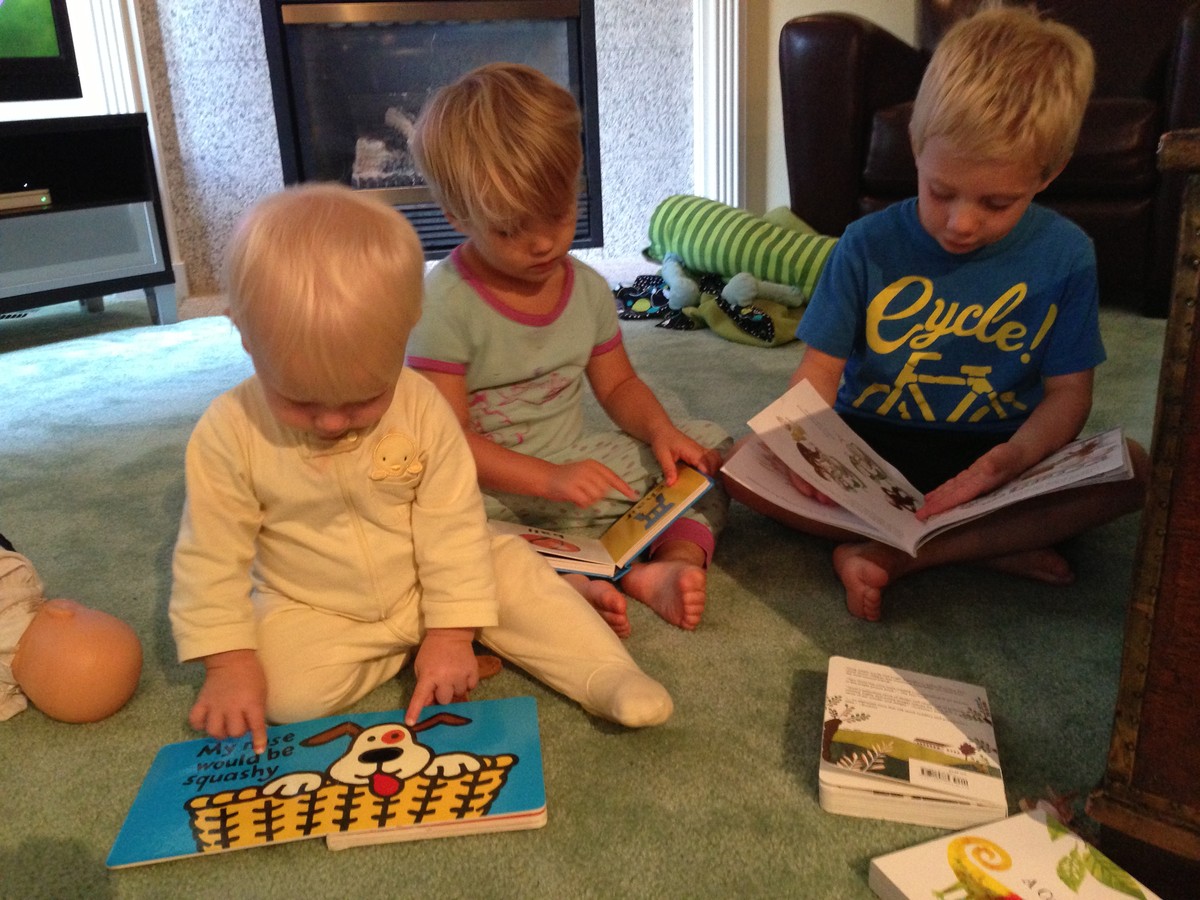

She made a point of differentiating them: Ada is bigger (!), has blond hair, and is filled in with color. They are also inside a house. A pretty complicated picture! I like to constrast this drawing with a photo we took at about the same time. This was during a period where the two girls were always together, often with attitudes like this:

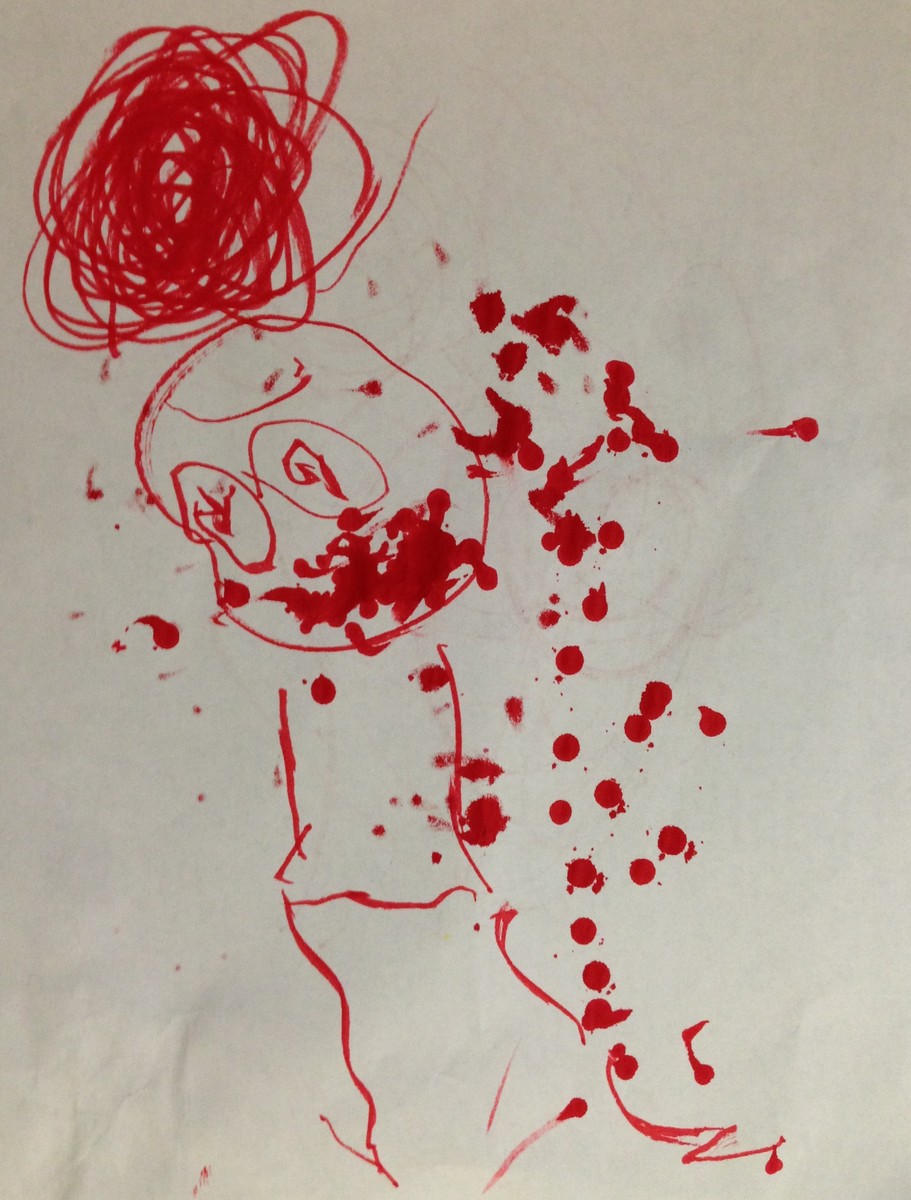

I have discussed Iris’ first piece of representational art elsewhere. It’s called “Daddy Fixing Bikes:”

The angry red dots are “Daddy’s disrespectful words.” Iris is conveying a lot of meaning in this picture, in ways that are both concrete and abstract.

I remember this incident very clearly. She was playing in the garage while I was recabling a bike. I made a bad cut; the cable end frayed; the fine cable strands pricked my fingers and produced a lot of blood. But what really set me off was that the bad cut unwound too much of the cable which meant I would have to start over. Thus the salty language. Iris saw all those drops of blood on the garage floor, just at the moment she heard me swearing.

Unfortunately we completely missed Orion’s first representational artworks. We were too inexperienced to know when a scribble might actually be a car or a monkey. I also hadn’t yet acquired the habit of taking pictures of his artwork, even when it was clear they represented real things. So I can’t say for sure, and have a thin memory of, his first such artwork. I remember him drawing objects and animals preferentially. I remember him drawing a “firetruck” and “helicopter” sometime around his third birthday. His drawings at that stage required a lot of explanation, which is probably why I wasn’t taking pictures of them. When he would point out that this line is a ladder and this line is a propeller, and this dot is a fireman, you could kind of see it, but otherwise it was scribbles. The first photo on my roll of a representational Orion original is a real whopper, a portrait of the whole family, from left to right: Iris; Daddy and Orion; Mama, Ada, and a dirty diaper: